Anas al Mustafa: Deportation without legal basis

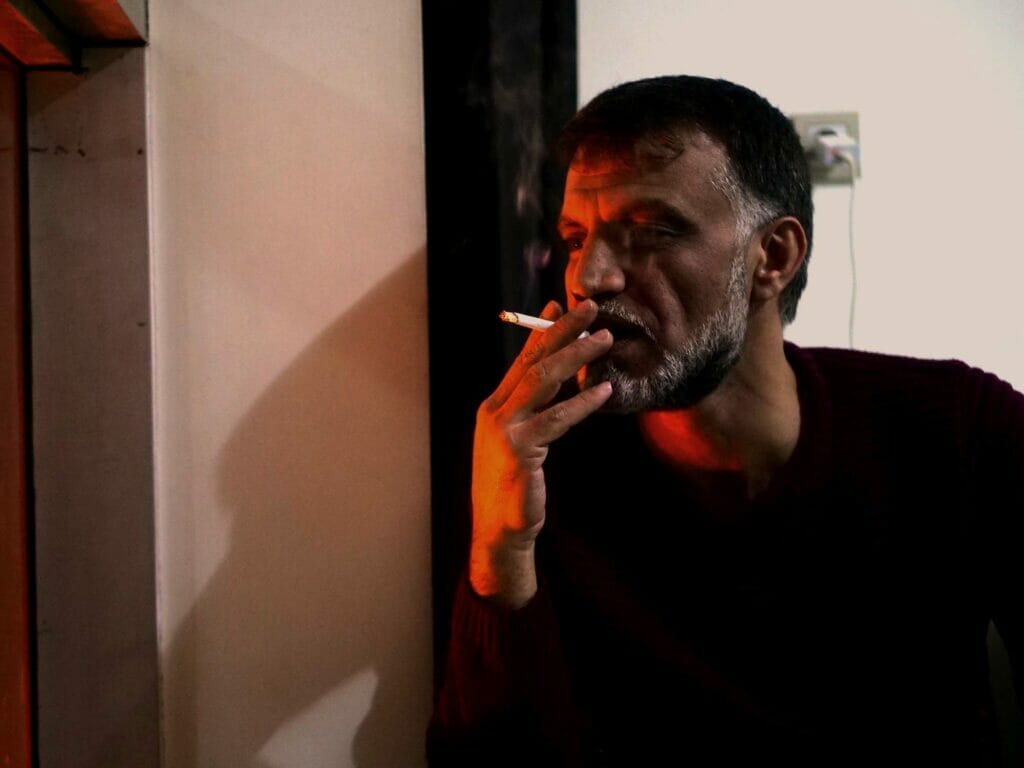

Anas al Mustafa does not necessarily walk fast, but quickly through Konya and knows exactly which streets and places he wants to avoid. Although many do not wear masks in public, he asks for it – to not attract the attention of the police. Even when he talks, he keeps an eye on the surroundings. Outside the area he wants to avoid, he then takes his time to explain sights. Actually, he wants to conduct the interview in an Arab restaurant. But in the short term, he changes his decision. There are secret services of different countries, he says. It is not safe to speak openly.

Arrested and deported for no reason

Der 41-Jährige muss generell auf der Hut sein. Zwar läuft derzeit ein Verfahren am Verwaltungsgericht, währenddessen er offiziell nicht abgeschoben werden kann, aber auf die Theorie ist hier kein Verlass. Das hat al Mustafa bereits am eigenen Leib erfahren, als er zunächst grundlos verhaftet, dann sieben Tage lang festgehalten und schließlich nach Syrien abgeschoben wurde. Dem Land, aus dem er einst vor Krieg und Gewalt geflohen war.

Currently, al Mustafa lives in a place that not even his lawyer is allowed to know. He does not have an official address. Friends pay for his accommodation, he is currently not allowed to earn his own money. He can hardly sleep, is always afraid that the police will be at his door again. Sometimes, he says, he doesn’t dare to come out for days. Runs back and forth in his four walls for days, immersed in thoughts and worries.

The reason for his hardships lies in his legal status: Officially, he does not live in Konya. Officially, he still lives in Syria. Officially, he has returned voluntarily and did not come back. But one thing at a time.

The most beautiful day becomes a horror day

It is May 15th, 2020, Ramadan, Lent. When the police knock on al Mustafa’s door, he initially thinks it should be his best day. “They kindly asked for my name. They asked for my Kimlik [Personalausweis](ID),” he says. At the time, his process for naturalization is underway, he should only go to the migration office for a short time to answer a few questions. “I was so happy,” he still says with a twinkle in his eyes. He puts on a pink T-shirt and white trousers; in Arabic a fashionable expression for a good day.

But the police does not take him to the migration office: “Suddenly they took me to prison. They took all my personal belongings, phone, money, everything.” No one talks to him. In the cell he meets five other Syrians, who meet the same fate, the same uncertainty. “One even drove by car to the prison,” says al Mustafa.

Seven days later, on May 22nd, 2020, al Mustafa finds himself in Idlib. Two days earlier, he had been forced to sign his voluntary return. “Do you know what they said?” he asks and immediately gives the answer: “That I voluntarily returned to my country on May 15th. I signed it on May 20.”

Five months in Idlib

The city is under the control of the terrorist organization Haiʾat Tahrir ash-Sham (HTS). He first has to go to the isolation center – the pandemic has also arrived in Syria. “I was really afraid for my safety,” says al Mustafa. Afterwards, he hides in Idlib. “I didn’t go outside. I was in contact with all my friends all over the world,” he says. Five months later, he decides to return to Turkey. A smuggler offers him the border crossing for 1500 euros. 30 hours walk. Without food, without drinking. In the middle of the dangerous mountains.

Anas al Mustafa crosses the Turkish border after a 30-hour walk.

First al Mustafa reaches Antakya, then he sleeps one night at a friend’s place in Reyhanli. Then he returns to his apartment in Konya. Two months later, the police asks his neighbors if he is back. On December 30, police knocks on his door again at five o’clock in the morning. “I called my lawyer and she said: Don’t open the door. They want to arrest you again,” he describes the situation. Now that he is in the country illegally, they have a reason to deport him again. That day he leaves his apartment and goes into hiding. For fear of getting into trouble themselves, friends and relatives now also avoid contact with him. “Before, my phone was like a central, I received messages and calls every minute,” says al Mustafa.

Anas al Mustafa helps Syrians in Konya

Until his deportation in 2020, al Mustafa is active as a humanitarian aid worker in Konya. When he arrives in 2016, he first earns money by setting up internet connections with a friend. Then he works for a humanitarian organization, which is now closed; he does not know why. During this time, he also builds up his international network. Friends now encourage him to continue to support the families. “First 20, then 50, then 100, 170, 175,” al Mustafa enumerates. He supported many widowed women, 400 (half) orphans. With food baskets or sometimes with the rent.

All this is no longer possible. “Now I feel like something without value. Why do they want to take that value from me as a human being?” he wonders. He had never been politically active or even said a bad word about Turkey. “When I came to Turkey, people welcomed us. I can’t forget that, I know that.” Now, however, he is treated like nothing.

After the interview, al Mustafa can hardly get out of his thoughts. Over and over again he repeats the injustice that has been done to him. He doesn’t understand. Later, he will show his shelter to strangers for the first time and also offer a hostel. Although he is tired and exhausted, he does not find rest. “I’m not just fighting for myself. I fight for all people who are wronged,” he says. Again and again he tells of the others who were deported with him and those who he knows have suffered the same fate: “Some of them had family, wife and children from whom they were separated!” He puts the chair at the window, one leg bent, the other placed on the heater. Smokes, shakes his head occasionally. He stares outside into the darkness, with empty eyes into the emptiness of the night.

Vorgeschlagene Beiträge

Syria’s torture prisons

Journalism in Turkey: Facts vs. Propaganda and AI

as-Suwaida under siege: “We can’t survive here”

[mc4wp_form id=239488]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.