“I was sure they were going to kill me.”

Zainab Entezar is one of the first Afghans to come to Germany through the Federal Admission Program. Here she tells her story.

A glass box symbolizes the pain. Zainab Entezar sits in a sporadically furnished room in Thurmansbang, Bavaria, with two beds pushed together to form a double, three lockers, a table and two chairs. The glass box filled with dried fruits stands next to a decorated photo. “I brought it to you to express something with it,” she says. The ornately crafted container had suffered some cracks on its journey from Afghanistan via Pakistan to Germany, Entezar explains:

“This is a symbol for us: if you look from a distance, everything looks good and beautiful; we are safe now. As you get closer, you see how broken and fractured we actually are.”

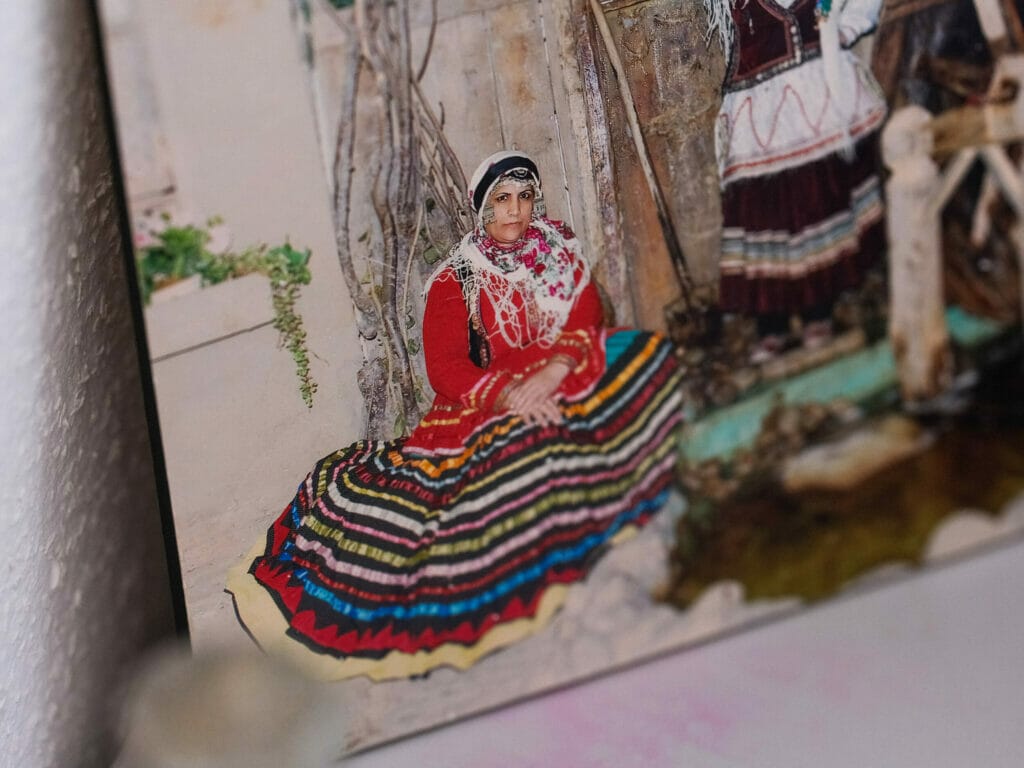

She looks around the room and points at various objects: The pictures, her camera with the two lenses, the notebook with four hard drives, the glass box, her traditional clothes… ” This is all I have left of my homeland. My whole life is in this room now,” says Entezar. As a result, she says, the first days in Germany were also quite terrifying; she felt what she had to leave behind – and who: “My family, my mother especially, is so far away now.” It is true that the trips between her residence in Kabul and her home in Herat, 800 kilometers away, also involved long travel times. “But we could always just visit each other,” Entezar notes. The new reality is entirely different, as she describes. “Now I don’t know when I will see her again.”

In the last week of September, the German government evacuated the first six Afghan:ins identified as being at risk to Germany through the Federal Admission Program (BAP). 2021, promised in the coalition agreement shortly after the Taliban seized power, the BAP was not announced until October 2022. After that, nothing happens for a year. Zainab Entezar is among the first evacuees.

In her room in Thurmansbang, she rummages through one of the lockers and pulls out a broken camera tripod: “This broke when I ran away from the Taliban. I was only able to protect my camera,” she says, making a hugging motion. Why she took the defective part? “Maybe I can use it for a movie,” she says.

Currently, two of them are in final editing: In one, Entezar addresses the women’s protests in Afghanistan, which continued under the Taliban against their misogynistic regime. It tells “a little bit about myself and especially about the ‘women heroes’ in Afghanistan.”

For her work, Entezar deliberately took the risks. She remembers one particularly memorable day: her young son had to go for vaccinations, which are mandatory at 18 months. Her husband had attended the vaccination appointment with him. She had been traveling in the city: “There were two women’s protests on the same day in different parts of the city. At one protest, journalists were arrested by the Taliban; at the other, participants were shot at.” Entezar was lucky; she remained unharmed and free. She comments:

I knew that I could have died. But I would never have forgiven myself if I had not documented the protests. I also had access to the places where women planned them and which were closed to other journalists.

Since February 2022, the 29-year-old has changed the city five times and her apartment eight times, always on the run from the Taliban. The terror rulers were specifically looking for the filmmaker because of her documentary work.other journalists and activists had long been arrested, one of her protagonists was shot by a Talib. “I was sure they were going to kill me,” she says – and that’s exactly why she filmed herself: “I wanted the world outside to understand what happened when I died and not forget all of us. People need to know that there is gender apartheid in Afghanistan and know all the crimes against women,” she says.

Belief in the power of the media

Who, if not she – a woman from Afghanistan – could be the voice for women of the country and carry their voices further? “I know what it’s like to be a woman in this country, and I have the opportunity to share those voices with my work.” Each of her previous works – several of which have already been broadcast at German film festivals – has dealt with women, she says; with true stories, sometimes retold and sometimes completely documentary.

Does she believe that movies can change the world? “Most definitely,” says Entezar, nodding with shining eyes, “The only, only, only thing that can really change the world is the media. Because how else do you find out what’s happening in the world, especially in war-torn countries like Afghanistan or Syria?” She sees film as the strongest medium for reaching people.

Entezar has been passionate about filmmaking since he was eight years old. She drafted her first small scripts and took a camera course as a 14-year-old. She taught herself everything else through YouTube videos; directing and script writing, for example. Her father did not like that at all. “When I was 16 years old, he told me if I ever made a movie, he would kill me,” she recalls. He was uneducated and could not even write his own name.

Then, anticipating, she apologizes for her choice of words:

“He thinks a woman who has anything to do with film is a whore.”

She gets loud:

“But I’m not a whore. I have responsibility, I’m a camerawoman, a director. I can pass on stories and people’s voices.”

Free life despite the resistances

Despite her father’s threats, Entezar did not let them stop her from realizing her dream. She began studying journalism at Kabul University in 2014, and that same year she released her first film: “Maryam,” the story of a young woman. Immediately afterwards, she followed up with “Home,” a work in which she autobiographically recounts how difficult it was for her to find an apartment in Kabul as a single woman. Once she and her friends were kicked out after only three hours, another time the tenancy lasted a year, then again only a few months. “It’s different in Afghanistan than in Germany: if you live there for rent, the owner can kick you out at any time. You have no security.” On top of that, the apartments were very expensive when they moved into them as women’s shared apartments.

The difficulties subsided as Entezar became more in line with social norms. “When I got married in 2018, everything became much easier; prices went down,” she recalls, “Marriage brings many such benefits to women in Afghanistan.” But at the same time, it carries risks. Entezar is currently writing her fourth book, in which she deals with the fates of three divorced women. Actually, a woman is not allowed to divorce in Afghanistan; she is then considered dishonorable. If a woman does dare to take this step, she faces many problems – up to and including murder by relatives.

And what else? By evacuating to Germany, Entezar escaped oppression and danger. Now the filmmaker is pursuing big plans again. She wants to travel to France to finish another film project she started in Afghanistan. With an apprenticeship, preferably in the media sector, she hopes to earn her own money quickly and learn the language. For her homeland, on the other hand, there is nothing left but dreams; she has no idea when anything could ever change there:

In my memory there is only war, in my mum’s memory there is only war, in my grandmama’s memory there is only war. We do not know peace in this country.

What does she say to people who claim that the Taliban at least ended the war? Entezar reacts angrily: “They kill people every day. Some directly. Others kill themselves. But if a girl kills herself because she is not allowed to go to school, or a woman kills herself because she is not allowed to go to work, then the Taliban have killed her, too. This is war too!”

She hopes that one day Afghanistan will be allowed to experience real peace.

The Federal Admission Program

It was supposed to bring 1,000 people to safety every month: That’s how it was announced, the federal admission program. Since its launch on October 17, 2022, however, little has happened in this regard. As of October 4, 2023, 13 people have entered Germany, and about 600 have received a promise of admission, the BMI press office said in response to a query.

Long wait for security

Entezar herself received her acceptance letter in March 2023, after initially unsuccessfully trying to apply for a safe country visa from February 2022. But the promise of admission was of little help to her at the time: Germany imposed a three-month ban on her leaving the country at the end of March 2023. The only thing left for her to do was to travel to Pakistan at her own expense and to look for accommodation for herself and her small family there, also at her own expense, in order to have at least a little more security. Previously, they had initially waited eight months for passports and another six months or so for their Pakistan visas – during these steps, the German government does not support even recognized persons at risk. After a security interview at the end of August, she was finally allowed to board a plane to Germany with her husband and son on September 26.

A press spokesman for the BMI states: “With the Federal Reception Program for Afghanistan, a long-term and structured procedure has been set up to enable the further reception of Afghans at risk.”

Since the start of the program, the new structures and procedures have initially become established – under highly complex conditions in Afghanistan, for example, without a foreign representation on the ground and the usual support structures. “With new forms of cooperation, especially close involvement of civil society, and a digital proposal process, the federal government has launched a completely new procedure,” he elaborates. In the meantime, 13 people have entered the country under the program (as of 04.10.2023). With the first arrivals, another important step has been taken towards the continued implementation of the program. Further entries are being prepared, he said: “However, the implementation of departures from Afghanistan continues to depend on many external factors which the German government can only influence to a limited extent. Considering this, it is also not possible to make a forecast on the number of departures.”

Post published on October 11, 2023

Last edited on October 11, 2023

[mc4wp_form id=239488]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.