Sergey Panashchuk: Reluctant war reporter from Odesa

Sergey Panashchuk works as a journalist in Odesa. In recent years he has tried to stay as far away from the war in Donbass as possible. Now the fighting has come to his city.

Sergey Panashchuk is someone who has a radar for people; especially for the total strangers on the street. When he approaches someone, a press quote is rarely turned down; actually everyone has something to say, even if it’s just something short. However, the 37-year-old shrugs off compliments on his approach: "That’s my job. I’ve been doing it for 18 years."

When we are traveling through eastern Ukraine with Panashchuk at the end of January, we try several times to praise him; it actually always ends with this – the same – saying. But this job has changed rapidly in recent weeks. For example, wearing a bulletproof vest, he reports from his hometown of Odesa or from Mykolayiv, 130 kilometers away, behind him alarm sirens and explosions from Russian cluster bombs just three kilometers away.

Poetry in the midst of war

Yes, he’s probably a war reporter now, says Panashchuk, but "not by choice," he didn’t choose it. Shortly after the beginning of the war, the weekly newspaper, for which we have previously reported together, asks whether he would contribute an article on the situation in the country. He asks if he can write in Russian and if we can have it translated. One of his strongest text, that I am familiar with, emerges. Highly emotional, yes, almost poetic. I tease him: You war poet. He replies again with "not by choice". And it’s obvious that he never wanted to have this profession. Although Panashchuk has lived in a war country since 2014, he still stayed away from the "hot war zones" as best he could when living in Odesa. As an employee for international reporters, he still knows what it’s like to suddenly be standing in front of a blown-up bridge.

At the end of January, Panashchuk still refuses to pass through military barriers in Popasna, and it takes a lot of persuasion to get him anywhere near what was then the war zone: up to Popasna, at the last tank barrier before the so-called contact line. In 2019, he completely rejected reporting from the "grey zone" to which Popasna belongs.

It’s getting a – admittedly somewhat macabre – running gag of our journey: We claim that we are now driving into the area that he refuses to enter. Finally, the serious compromise is to only use routes in the vicinity of trenches and minefields where snow tracks are clearly visible. And he can seriously laugh about the radio channel in one of the occupied territories, the self-proclaimed and internationally unrecognized Donetsk People’s Republic with the beautiful name "Radio Daddy Donetsk". He laughs tears on the passenger seat when the particularly deep male voice recites the radio advertising slogan.

Blinded by serenity

The threat seems to be at least forgotten in these moments. Rather, we concentrate on the numerous potholes of the road on which we drive. Even we, as foreigners, are gradually letting the residents of eastern Ukraine convince us, that our worries of a large-scale war are exaggerated. We are even insulted once, we – the West – should stay out of it. "Would you kill your brother?" says the Ukrainian interlocutor angrily; Russians and they are brothers. The conversation takes place in the border town of Vovchansk, which has now been taken by the Russian army. But at that point in time we doubt ourselves whether we might have succumbed to remote hysteria.

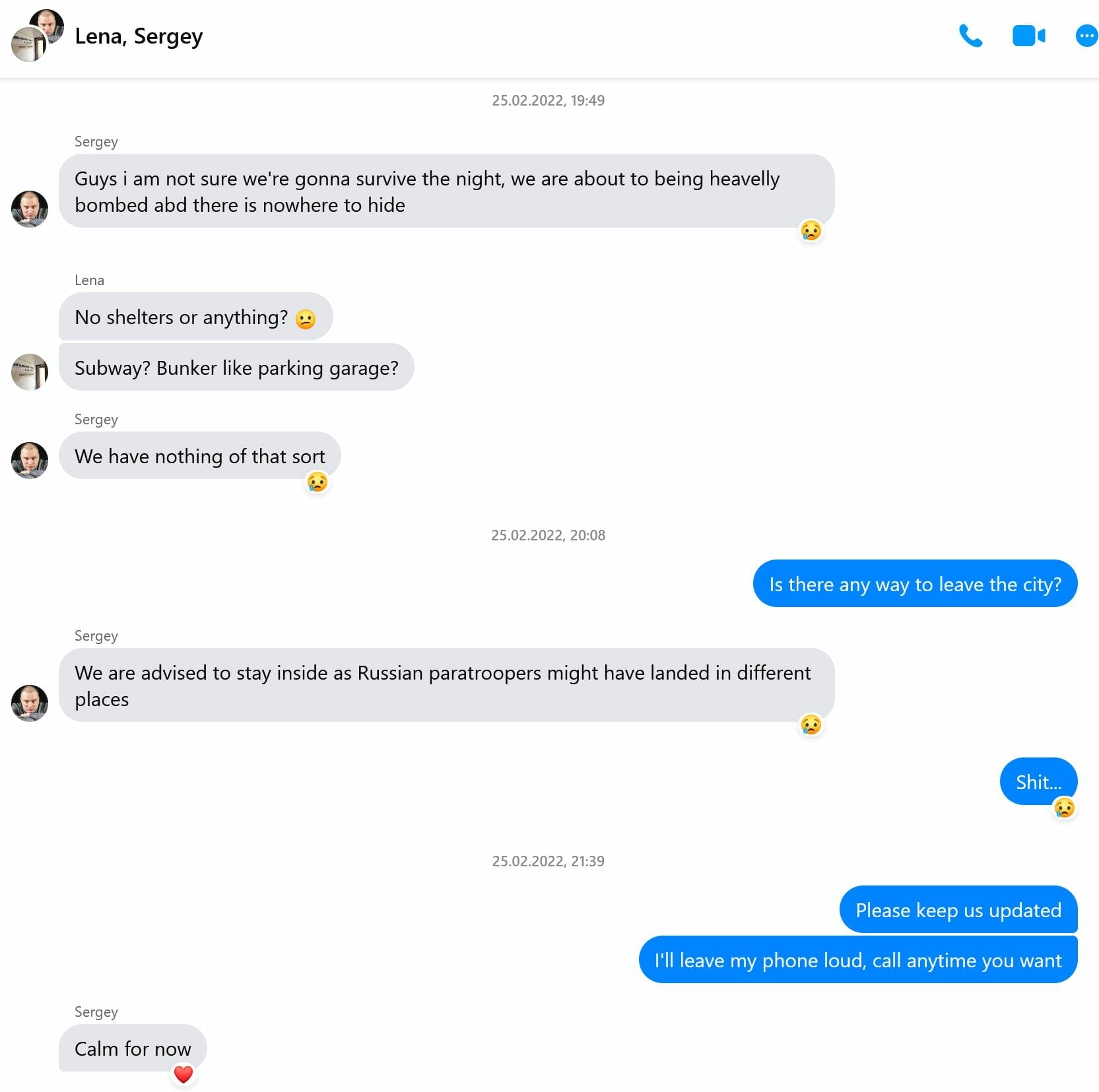

Then, with the Russian army’s full-scale invasion on February 24, the war comes to Panashchuk. Air raid alarms are now part of his everyday life. On one of the first evenings of the war he even says goodbye to us. "I’m not sure we’ll survive the night," he writes on the evening of February 25; the second day of Putin’s war of aggression. There is no bunker that he and his wife could reach. He sends us a photo of two construction helmets, with which they try to protect themselves at least a little.

Between fear and sarcasm

Panashchuk now reports from his hometown and the neighborhood wearing a bulletproof vest, and even works with international journalists when they travel deeper into the war zone. He can be seen on a live call with a British TV station; reports that he saw civilian victims of the Russian war of aggression with his own eyes: "Their corpses, the blood." Three of them were hit and killed in front of a supermarket. "They just wanted to buy groceries," he comments.

As serious as he is in front of the camera, there is still room for humor in the group chat. Between the fear of war and death, there is still room for sarcasm and black humor. Still, it’s hard to bear to watch him from afar at his unwanted new focus of work, knowing that he can’t even run away from this war. As a man of military age, he is not allowed to leave his home country.

Vorgeschlagene Beiträge

Kharkiv: Victory on ruins

Fled from Ukraine: “I have no more tears.”

How Stanislava Liasota started Ukraine’s first musical group

[mc4wp_form id=239488]

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.