Earthquake in Hatay: “Not even to get help, there was media freedom”

Hatay about three months after the severe earthquake: there is surprisingly little sign of construction work, rubble is still piling up next to the collapsed houses, sometimes heaps of rubble have been collected. Fully furnished rooms stand out behind the lack of facades. Survivors have moved to relatives in the village or are living in tents. Right next to one of the tent camps in Defne, helpers are sitting in a warehouse where all kinds of donations are piling up. Outside of the building there is a mural commemorating the three people who were killed in police operations: Ali Ismail Korkmaz, Abdullah Cömert, Ahmet Atakan. One of the volunteers inside is Feray Aytekin Aydoğan, board member of the left Sol Party.

Aydoğan describes how emergency aid for people who were still under the rubble in Hatay was blocked by the government. “Some wanted to tweet where there were survivors so they could be searched for. But after just a few days, social media was only accessible via VPN,” she explains, “there wasn’t even freedom of the media to get help.”

Freedom of Speech and Media in Turkey

The media and Freedom of expression in Turkey is severely restricted. At protests, you always have to expect that you will be arrested. “That’s part of it,” says Aydoğan, who has been involved in party politics since she was 18; at that time for the forerunner of the Sol party. Because of the state repressions, hardly any people expressed their opinion publicly: “Now they are even afraid to tweet something about the government.”

Aydoğan confirms that the impression is not misleading and that the construction work is completely idle in many places or has not even started yet. There were volunteer offers, but volunteers had to keep their hands off many buildings; for protection reasons:

A lot of asbestos was used here in Hatay. This is a huge problem. Asbestos is toxic and can cause disease.

So far, there has been no solution as to how the material can be safely removed and disposed of. Until then, nobody can work on the affected buildings and rebuild them. The rubble also poses a health risk for the tent dwellers. “In the beginning, people pitched tents right next to their houses,” she says. However, the risk was then identified by experts. Since the exposed fibers could also reach the tent dwellers, people had to change their location.

Waiting for help in earthquake area

Those who have a second home or relatives in the villages that are less affected have now moved there. But many would only have had their home in Defne and now persevered and hoped for help – so far mostly in vain.

As a teacher, Aytekin Aydoğan is primarily concerned with dealing with education. “In some schools that are half destroyed, classes are still taking place,” she says. Some of the lessons also take place in containers, but mostly in places that are not safe, but rather in danger of collapsing. That poses a big problem.

Sympathy before qualification

Feray Aytekin Aydoğan has actually studied physics to become a teacher for secondary schools, but is only allowed to teach mathematics as a primary school teacher. That’s because teacher jobs are assigned by the government – and sympathy can decide career opportunities. “The fact that I’m a woman, that I’m not a Muslim and that I’m with the Sol party speaks against me, all of which causes problems,” she explains. On top of that, the government doesn’t have much to do with natural sciences anyway: The theory of evolution has even been removed from the curriculum, and natural science subjects have been severely restricted. Instead, religious topics would be given more space in the classroom.

Otherwise there is a lack of important infrastructure. The hospitals in the Hatay region were hit particularly hard, with some of the buildings showing serious defects even before the earthquake. “Emergency clinics have been set up, but they can hardly be reached from here,” she explains.

Loans from the government

In general, the people in Hatay felt let down by the government. Instead of real support – “Housing is a task of the state!” – the government offered people to build their houses against a loan: “But people don’t want to go into debt.” In addition, the government is partly to blame for the extent of the destruction caused by the earthquake: “Instead of real experts, religious people are used for everything. This has consequences: roads are built where they shouldn’t be built, buildings are built where they are not safe and even airports are built where they shouldn’t be built.”

Aydoğan fears that there may not be a solution before winter. Tents are not a solution when it gets colder again. Containers are needed, and well-equipped containers at that. Currently, these are only available in more distant areas. “But the majority of the people who are still here now have to stay here. The area is heavily agricultural; people have to be close to cultivate their fields,” she explains. Many therefore refused to move away from Defne to the actually more comfortable transitional quarters.

Life in the Park

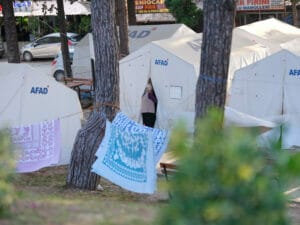

In one of the tent camps in Defne, people have been living in the tents of various aid organizations for months. It’s quiet there, occasionally a child is playing in a meadow. Around the park are destroyed buildings; in the park itself rows of tents.

In front of one of the tents, Melda has spread out dolls and toiletries on a bench and a table. “I had a business before the earthquake,” she says. That is exactly how her house is now destroyed. Shop operations recovered after the corona pandemic and things got better again. But then came the earthquake. She now sells the products that are left over here, a small selection of her former range. “People buy what they need,” she says, pointing to deodorant and shower gel. Does she see any prospects for rebuilding her house? “Unfortunately, I don’t know when that will be possible. It is currently illegal to go into houses and do something yourself,” she says.

No perspectives in Defne

Meryem also lives with her family a little further back in Atatürkpark, which borders on Hidropark. She recently received an offer to move to a container village just outside. “But I don’t want that; I like to stay here near our home.”

It’s difficult to start a new life here. It is practically impossible to find work from here. Even before that, Meryem didn’t earn much, she worked as a cleaner in private houses. Now she and her family live off the small amount the government provides for food and necessities.

On a drip from the state

The situation is similar for Semira and Ali Duman, who live in tents here. “We are completely dependent on the government’s help,” emphasizes Semira Duman. However, many of the donations in kind did not reach them at all; there is actually a lack of everything: clothing, underwear and more. She has been living here for two months now. Before that they had found accommodation at their own expense, but the money eventually ran out.

How long will the situation remain like this? She looks sad and angry: “So far we have not received any money from the government to rebuild.” Ali Duman explains that there is an offer where you should pay 40 percent of the construction yourself, so you have to go into debt with the government. He doesn’t think that’s any real help: “The government is letting us down.”

A sad picture

Tent neighbor Nuretin Eskiocak joins in the conversation, describing that he lost a daughter and his grandchildren in the earthquake; his daughter’s children. Before that, the situation wasn’t really good either, but better. Now there is no more perspective.

On the further tour, the picture is almost the same everywhere: Destroyed houses, people in tents, a few people trying to save half-hearted things from the houses – contrary to a ban that was issued against it.

One of these groups eventually stops the military police. Elsewhere, Bekçi, known as Erdoğan’s militia, patrol. However, reporting and photography is not hindered.

Vorgeschlagene Beiträge

Syria’s torture prisons

Nusaybin: In constant fear of the state

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.